|

I

lifted one plastic boot and planted its steel crampons into

the snow with a styrofoam crunch. I took a deep breath. Fourteen.

Eleven more steps and I could rest again. I

lifted one plastic boot and planted its steel crampons into

the snow with a styrofoam crunch. I took a deep breath. Fourteen.

Eleven more steps and I could rest again.

It was

dark, the air was thin, and Billie Holiday crooned through

the ice-coated wires of my headphones about what a little

moonlight can do.

The night

clouds parted and the snowy flank of Cotopaxi, the highest

active volcano in the world, was bathed in a spectral light.

I was almost

exactly on the equator, three miles high in the heart of the

Ecuadorian Andes, with three thousand feet to climb before

dawn.

Ecuador

is slowly gaining fame as a high-altitude playground where

mountaineers can cut their teeth on peaks up to 20,000 feet

with relatively little expense or effort. Many of the climbs

are not technically difficult, but up here a world away from

the country’s sweltering rainforests and Pacific beaches,

even a walk in the snow is nothing to be taken lightly.

We had

met the day before in Quito, which at 9,375 feet is the second-highest

capital in Latin America. There were four climbers—my

friend Jeff and I, quiet David from England, in Ecuador to

adopt a daughter, and Adam, a talkative chemical engineer—and

two guides: copper-skinned Ramiro, who owned the climbing

company, and Juanito, who had a Wile E. Coyote doll strapped

to his backpack.

The

perfect snow-capped cone of Cotopaxi poked above a layer of

clouds as we left the city smog for the Avenue of the Volcanoes,

Ecuador’s knobby Andean spine. The

perfect snow-capped cone of Cotopaxi poked above a layer of

clouds as we left the city smog for the Avenue of the Volcanoes,

Ecuador’s knobby Andean spine.

At 19,400

feet, Cotopaxi is the second highest mountain in Ecuador,

and by far the most popular to climb. Its name means "Neck

of the Moon" in Quechua, the language of the Incas, Ecuador’s

first inhabitants.

One of

the most destructive on the continent, Cotopaxi has a rap

sheet of over a dozen recorded eruptions. It last blew its

top in 1877, which was recent enough for it to be considered

the highest active volcano in the world.

A rough

cobbled track led toward the north side of the mountain past

cows and half-wild horses grazing in the intense equatorial

sun. We parked above the treeline and gasped our way up a

gravel slope to the climber’s refuge at 16,000 feet.

The stone building that smelled of exertion and starchy food.

Ramiro

took Jeff and I out onto the glacier for a short course in

traveling over ice and snow. He showed us how to walk diagonally

to keep from shredding our calves with the spikes of our crampons,

and demonstrated how to stop a sliding fall.

"If you

fall, get your head uphill and dig in with your ice axe, like

this." As I practiced, I wondered if I’d have the presence

of mind to do that as I careened down an icy slope in the

darkness with a brain starved for oxygen.

Back at

the refuge we ate dinner amid an Indiana Jones atmosphere

of candlelight and a murmur of languages. The plan was to

leave at 2 a.m., in time to be well up the mountain before

the sun started to soften the snow.

I fell

asleep hoping I had what it took—mostly determination

and luck—to be one of the one in ten that made the summit.

I woke what seemed like every few minutes gasping for breath,

my mouth so dry my tongue split.

We dressed

in the darkness, stuffed down a quick breakfast, and assembled

on the flagstone patio for a final gear check. Ramiro tied

Jeff and I to his rope and set off up the slope. I put on

my headphones and listened to Billie Holiday sing of starts

falling on Alabama as the headlamps of other groups bobbed

uphill in the darkness.

We

hit the snowline within an hour and strapped on our crampons.

David had turned back mysteriously just above the refuge,

but the rest of us still felt strong. We

hit the snowline within an hour and strapped on our crampons.

David had turned back mysteriously just above the refuge,

but the rest of us still felt strong.

The sky

began to lighten to the east as we cut endless switchbacks

up the northern route pioneered in 1882 by Edward Whymper,

the first man to climb the Matterhorn. Robin’s-egg blue

gave birth to strips of lava, then half a skyful of flaming

feather clouds.

Soon our

guides’ slow but steady pace began to take its toll.

We were closing in on 18,000 feet, where the air holds half

as much oxygen as it does at sea level. I had the advantage

of a month in Ecuador already, but the rest had arrived more

recently and hadn’t had much time to acclimatize.

Jeff switched

to Juanito’s rope and I turned up the volume on McCoy

Tyner playing the piano like a man with twelve fingers. I

let the swinging chords fill my mind and drown out all thoughts

of stopping.

On non-technical

ascents like this, climbing is a much a mental challenge as

a physical one. The trick becomes knowing when to listen to

the inner voice begging you to stop, and when to ignore it

and push higher.

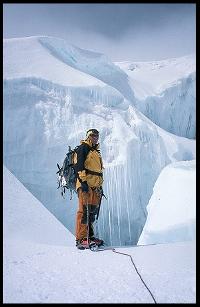

Ramiro

and I stepped over crevasses that fell into blackness and

climbed past ice caves glowing blue in the sun. The world

was nothing but snow and sky, purple shadows and the yellow

dot of Ramiro’s parka.

The incline

grew steeper the higher we climbed and the summit seemed to

recede into the wind-whipped air. Existence had narrowed to

a simple rhythm. Step. Gulp air. Plant ice axe. Repeat.

My head

pounded. I would have given anything to sit down in the snow

and stop, and probably would if I could hear my inner voice

more clearly. I turned up the volume.

Suddenly

the slope flattened and the trail ended at the lip of a vast

crater filled with clouds. Ramiro turned and grinned and congratulated

me for being the first person on top this fine morning.

I looked

around in a daze, grinning through my frozen beard.

My mouth

didn’t seem to work quite right, but I almost laughed

when Ramiro pulled out his cell phone to call the office and

tell them we had made it. This was his 143rd time

on top.

The wind

whipped the clouds apart to reveal peaks in every direction

as we snapped photos of each other, axes raised. Then we turned

and started down.

The descent

took less than two hours. The sun, still rising toward noon,

softened the snow and inspired us to strip off layer after

layer of clothing.  Wonderful oxygen filled the air. Wonderful oxygen filled the air.

We slid the last

thousand feet to the refuge on the seats of our pants, whooping

like cowboys.

TRIP ESSENTIALS

Cotopaxi is 50

km southeast of Quito, the capital of Ecuador, in the center

of a national park of the same name. It isn’t a technically

difficult climb, but it’s not for the inexperienced or

unprepared. Basic mountaineering gear is essential, along

with moderate climbing experience or the services of a trained

guide.

The best months

for climbing are December and January, followed by August

and September. You should definitely acclimatize with a week

or two in Quito (at 9,400 feet, the second highest capital

in the Americas) or higher before attempting the ascent. Ecuador

has plenty of smaller mountains for training climbs: try Atacazo,

Corazón, Guagua Pichincha, Ilaló, Imbabura,

or Pasachoa.

It costs $10 per

person to enter the park and another $10 to spend the night

at the José Ribas refuge, which is administered by

Alta Montaña in Quito (tel. 02-2254-798

aventurag@ch.pro.ec). The

two-story shelter has 70 bunk beds, lockers, cooking facilities,

running water, and snacks and water for sale.

There are dozens

of climbing companies in Quito that can take you to the summit

for $150-200 pp, all inclusive. Two of the best are Ramiro

Donoso’s Ecuadorian Alpine Institute at Ramirez

Dávalos 136 and Amazonas, tel. 011-593-2-565-465, fax

011-593-2-568-949, EAI@ecuadorexplorer.com,

www.ecuadorexplorer.com/eai,

and Safari Tours at Calama 380 and Juan León

Mera, tel./fax (800) 434-8182, 011-593-2-220-426, fax 011-593-2-223-381,

admin@safari.com.ec,

www.safari.com.ec.

You

can get the latest climbing conditions, along with just about

any other travel tidbit imaginable, from the South American

Explorers’ clubhouse in Quito at Jorge Washington

311 and Plaza, tel./fax 2-225-228, explorer@saec.org.ec,

www.samexplo.org.

Membership is $40 pp for a year ($70 for couples).

The best guidebook

to the country, of course, is my own Ecuador Handbook

(Avalon Travel Publishing, $16.95), which was fully

updated in 2000 to include the country’s recent switch

to the U.S. dollar.

Yossi Brain’s

Ecuador: A Climbing Guide ($16.95) and Mark

Thurber and Rob Rachowiecki's Climbing and Hiking

in Ecuador are available from The Mountaineers Books:

www.mountaineersbooks.org.

|